Staffordshire

I am using this term in a very general and admittedly inappropriate way (although I’m not alone in doing so) to refer to my small collection of British earthenware (and a few porcelain) cow creamers dating from the 18th and 19th centuries (with a few early 20c). Very recent ones with similar shapes and styles are for the most part covered either under the manufacturer (e.g., Kent, which has adopted some of the older molds from creamers shown here), or under ‘Places’, or just lumped in with all the other modern creamers.

The main English centre for producing pottery cow creamers, starting around 1740 with saltglazed stoneware, was Stoke-on-Trent and vicinity (which is in Staffordshire, thus the general term). Stoke-on-Trent is made up of six distinct towns: Tunstall, Burslem, Hanley, Stoke, Fenton and Longton - collectively known as "THE POTTERIES". See their web site, www.thepotteries.org, for lots of good basic information on the area, the potteries, potters, etc.. However when cow shaped creamers and spill vases became popular, inspired at least a bit by Schuppe’s silver ones, other pottery centers – notably in Tyneside, Yorkshire, South Wales and South Scotland -- also began producing them, in part because Staffordshire potters moved to these areas to establish or run factories. I have trouble distinguishing creamers from these other centers from those of Staffordshire, unless the seller provides information. One exception is the Swansea, South Wales creamers, many of which are quite distinctive. I have therefore included a description of these Welsh potteries and their cow creamers down near the end of this page. I have also added a section dealing with Spill Vases, many of which used the cow creamers as part of their decoration.

My collection pales in comparison to the fabulous Keiller Collection in the Stoke-on-Trent Museum Art Gallery, but I do have a number that I’m quite fond of. One problem with these creamers – as indeed with any ‘figures’ of the period, be they of people or animals - is that not many of them have a well established provenance. Such is the case even with the Keiller collection – I believe that only three of the 667 in that collection have the maker’s name impressed. As opposed to silver creamers, where hallmarks and assays are the norm (and generally required by law as well as by the guilds), most of the early pottery creamers don’t have marks or any sort, and since they were basically common household items, the maker was of little importance to the buyer. I will give as much information as I have, but in general I have found that the sellers – even ‘Staffordshire’ experts – don’t have much information. I welcome any and all help in improving my attributions. One other note is that most of these creamers have restorations of some sort, although in most cases they have been carefully done by professionals and are hard to discern. The need for restoration isn’t surprising, since the horns, tails and ears are quite fragile (except for when they were cleverly smushed down onto the cow’s head or body), and these were made for daily use more than for display.

Cow creamers were, of course, only a very small component of the wares produced in Staffordshire, which had been noted for its potteries for hundreds of years. Most pieces naturally were simply utilitarian – bowls, pots, plates, etc. Starting in the 1700s, in keeping with the overall trends of industrialization in Britain, the potteries became more mechanized and organized, and so they remain today although there has been an almost infinite number of changes in process as well as ownership and organization of the firms. There are a number of good sources for the potteries history, but for a short version I’d suggest http://www.historynet.com/potteries-of-staffordshire.htm . At around the middle of the 18th century, in response to a growing demand for both quality and decoration, the potters began to complement their functional items with figures of people and animals. Not unnaturally some of these more fanciful items also were designed to serve useful purposes such as holding spills, and – after they became popular – serving milk and cream. For a brief introduction to the art of the very popular (and still very highly sought by collectors) Staffordshire figure, try http://www.adelekenny.com/-staffordshire-figures.html. For those who want a more in-depth treatment, I can heartily recommend Pat Halfpenny’s excellent book, "English Earthenware Figures, 1740-1840", published by the Antique Collector’s Club and available through a number of used book sellers both in the UK and the US.

As a side note, as well as a reminder to myself next time I go trolling for cows through the English countryside, there’s a web site that provides frequently updated information on traffic on motorways and common A/B roads: www.frixo.com

One more note – I use museum putty to hold the lids on. I first encountered as blue-tack it in London in 1995, where it was used to hold up the pictures of call-girls in the phone booths. It seems to hold quite well for several years without hardening or leaving a mark, which is presumably what endeared it to the pimps and made the practice tolerable to the police and phone company (albeit in more recent trips the practice seems, sadly, to have faded). It shows in many of the pictures. If anyone has any better suggestions, I’d appreciate it.

|

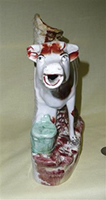

This is my favorite – a very lovely model of a cow and calf with boscage or bocage…a term for leafy decoration on pottery of this era; I have seen this style referred to as “Walton School”,after John Walton. I bought this creamer from the London store of Oliver-Sutton antiques in Kensington (they have since closed), who attributed it to Tittensor, circa 1780. Tittensor is both a family name, and the name of a village in Stafford, between Newcastle-under-Lyme and Stone. Although information is sparse, it’s most likely that this creamer can be attributed to Charles Tittensor, who was a small scale potter who specialized in bocage and other earthenware figures, working in Shelton in the early 19c, and who had a number of different partners over the years. The date I was given by Oliver-Sutton is almost certainly incorrect both because (as noted by Pat Halfpenny) Charles Tittensor was not recorded as a potter until after the turn of the century, and because bocage was not introduced until around 1810-1815. Given the uncertainties, I’d simply say that this lovely underglaze painted piece is from the first quarter of the 19c. |

|

|

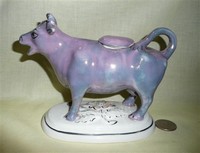

Here is another favorite, a pinklish splash Sunderland lustre creamer in perfect condition that I acquired in early 2013 from John Howard of Woodstock, an Antique English Pottery Specialist, just as he was shipping it to New York for a ceramics show. Unlike the Tittensor one above, however, the maker is unknown – John could only tell me that he acquired it in Burton on Trent, and that it was manufactured in Staffordshire around 1820. He did note however that this is a very rare example, and in his four decades in the business it is one of the few that he has seen with no restorations or damage. At the time it was made, luster ware was at or near the top of the market for earthenware figures, so I can only imagine that the original owner either bought it more for decoration than utility (like the Tittensor piece that would be too unwieldy for daily use), or at least used it on only special occasions. Certainly most of my others have not fared nearly so well as this beautiful cow. |

|

|

|

|

|

I was delighted to find this third lustre cow offered on Ebay, said by the seller to have been a favorite of her antique-dealer mother. Basically the same as those above, the purple coloration and mold are identical while the markings are somewhat different. This one has had horns, part of the ears, and tail restored, and it has a replacement lid - all nicely done but darker than the body, perhaps due to age. |

|

|

I purchased this early green and white cow creamerfrom Oliver-Sutton in London at the same time as I acquired the Tittensor. It was identified by them as a Whieldon, circa 1780, and bears an old inventory #509 from the C.B.Kidd collection. Thomas Whieldon (1719-95) of Fenton Low, Stoke-on-Trent, was a Master Potter who – according to the Famous Potters page from that town (www.thepotteries.org/potters) taught both Josiah Spode and Ralph Wood, and from 1754-1759 was in partnership with Josiah Wedgewood. There is more information about him a couple sections down. This creamer has a ‘mushroom’ handle on its lid, which like some other very early ones, has simply been cut out of the back of the cow rather than being a separately fashioned plug.ood. I have spent some time on the web trying to find out more about the C.B.Kidd collection, since not only do I have some pieces from it, but they seem to have been offered (at high prices) by quite a number of knowledgeable antique dealers over the years. Courtesy of Robert Walker of Polka Dot Antiques I have learned that Captain Charles Bernard Kidd was born in 1880 in Dartford, Kent, and educated ‘privately’ and at Cambridge. He was a keen hunter of hounds and was Master of Foxhounds of the Southdown Hunt from 1910-1913, which post he relinquished when he accepted a commission at the beginning of WWI. He was a well known collector in the early 20c, and his collection was likely sold by Sotheby’s in the 1950s. |

|

|

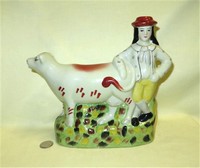

This finely potted creamer with milkmaid was ascribed by the knowledgeable seller, Andrew Crowley of Liverpool, to Thomas Whieldon, circa 1760, and acquired by him from the “wife of a construction baron (recently deceased) from her Georgian townhouse in the Chelsea area of central London. The pottery pieces were mostly Whieldon and yorkshire Creamwares, with the collection there was an inventory book, which indicated that this creamer was purchased in 1972 from an antique shop on the nearby Kensington church street.”…which just happens to be the location of Oliver-Sutton’s shop. His description notes “the cream coloured earthenware body covered in coloured glazes derived from manganese, copper, cobalt, iron and antimony. The colours were sponged onto the body and then covered with a clear lead glaze, the subsequent firing caused an intermingling of the colours, this type of ware is also called Tortoiseshell ware.” This jibes well with what I have recently read about Whieldon in Pat Halfpenny’s excellent book, "English Earthenware Figures, 1740-1840".. This early creamer does have a bit of damage – a chip to its lid and one to the left ear showing the creamware of the figure, and some nicely done restoration to horn tips and the milkmaid’s right arm. Overall it’s a lovely early example. |

|

Here is a third that was attributed to Thomas Whieldon (by a faded sticker under the base), in this case 1770-1780. The base cow is indeed quite white, and the colors are typical of the era. I really have no way of verifying that any of these three are actually from Whieldon – but if so, he was a master of many styles. |

|

|

Usually I look for bargains on eBay, other sites, and antique shops. On occasion howevere - like with the first of my Sunderland Lustre cows above, I find some on major antique dealers' sites that I just can't resist. That recently happened with this early creamware cow, and two others that are in their appropriate slots below. They came from Martyn Edgell Antiques, Ltd - Antique British Pottery & Porcelain of Nassington, Peterborough, UK. He states that it is creamware with underglaze brown oxide decoration, is "Whieldon type" and dates from @1770, making it one of my oldest earthenware creamers,friom the same period when John Schuppe was selling is silver ones to the gentry. I was fascinated by the bird on the lid - albeit it has had its head and tail restored, along with a repaired tail break on the cow. This little guy has 'crossed the pond' at least twice, since it was in the stock of Wynn Sayman of Richmond, MA before it came - presumably via another collector - to Martyn Edgell. I'd like to think that it actually may be by Whieldon, since it is certainly in his style and there weren't all that many potteries turning these things out at that early date. |

|

|

This selection of three creamers is a good place to say a bit more about styles of early English creamers (and other figures). All three here are multi-colored underglazed pottery – the one in the middle, like the one with green coloring above, has an incised lid, and came from the Kidd collection via Oliver-Sutton shop which called it ‘Whieldon-type’. From its coloration it could be termed Creamware. I believe it’s quite early, say mid 1780s, from before folks started making round holes in the top and fashioning separate plugs. The two surrounding it are whiter in color, thus pearlware (see feature articles at www.thepotteries.org for some good information if you can’t find a copy of Pat Halfpenny’s book); presumably the clay in the body is whiter (no breaks on these so can’t be sure), and the glaze is tinted with cobalt=oxide. They are also 18c, sold to me (at London antique fairs) as being from around 1790. All three of these cow creamers could be termed ‘Pratt Ware’ or ‘Prattware’, which as noted above became the generic term for underglaze colored cream and pearlware that was made rather widely in the UK from about 1785 to 1840. The best information source on these that I have found is “Pratt Ware – English and Scottish relief decorated and underglazed colored earthenware 1780-1840” by John and Griselda Lewis. From there we learn that there was a Pratt family of potters “who were working at Lane Delph in the late eighteenth century and also at Felton after 1807”. The term Pratt Ware however wasn’t used until the early 20c, when a couple of rival authors coined it based on a very few multicolored underglazed jugs with relief decorations that bore the Pratt name and were in the prototypical style. So the Pratts have been memorialized rather by happenstance, with their name applied to wares made by hundreds of potteries over a span of decades. The Lewis’ book has hundreds of pictures as well as fascinating articles about the Pratts, how the wares were made and colored, and the many locations where this style of decoration was employed until it was surpassed by overglaze enamel colored wares and other techniques that became popular in the early to mid 19c.

Here are frontal shots of these three cows to show the shape of

horns and mouth.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Here is yet another early Prattware example, this one missing its lid but otherwise in fine condition.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

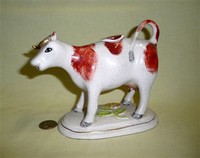

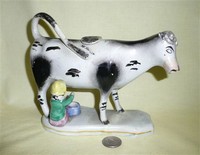

This pearlware black and white cow, that I bought from Martin Edgell Antiques, was said by him to be "possibly" St Anthony's Pottery, Newcastle-on-Tyne, circa `1820. It bears such a striking resemblance to one that I have seen with markes (as few were) for that pottery, that I decided to it to my collection so that I had an example from there. From twsitelines.info/SMR/4194 we learn that "The pottery at St. Anthony's was established in 1780, possibly built by Thomas Lewins. James King & Co who were also interested in several glass works, were probably the first lessees and potters. In May 1784 the pottery was damaged by fire. In 1786 James King was bankrupt. In 1787 Chatto and Griffith took over the lease, but William Chatto was bankrupt by 1795. William Huntley took over. In 1800 the pottery changed hands again, taken over by Foster and Cutter. St Anthony's Pottery was bought by Joseph Sewell from Foster and Cutter around 1821. He made earthenware, creamware, queen's ware and gold, silver and pink lustreware, pierced wicker baskets and filigree plates. Sewell had a flourishing trade with the continent, principally in pink lustreware jugs. The firm's successors were Sewell and Donkin (from 1821) and Sewell and Company (from 1853). They also made transfer-printed wares, doll's tea sets. Creamware tea and coffee sets, printed with black or red Danish motifs, such as buildings in Copenhagen or Elsinore, scenes or portraits, were exported to the continent. When the company closed in 1878 some of the stock was bought by J. Wood of the Stepney Pottery. Ordnance Survey first edition shows workers cottages in an L shaped named St. Anthonys Square and unnamed cottages to the south. By the second edition the northern complex has been renamed Pottery Square and the southern are Pottery Cottages." I think she is quite handsome, with excellent professional restoration to the lid, horns and ears, and really makes a nice addition to my copllection. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

This is a relatively simple flat based cow creamer from @1820. It has restoration to the horns and tail and a replacement lid, all very well done. |

|

|

This beautiful cow with calf on a flat green base with canted corners dates from ~1810, and is most likely Scottish (the seller stated that the red sponged pearlware is typical of Scotland) of from the north country. It has had some well done professional restoration to the horns and is missing its little lid, but I find it lovely nonetheless. |

|

|

|

This ‘Prattware’ creamer – with a restored tail and lid and broken horns, probably made around 1790 – was said by the seller (who has kept a very similar one) to have been bought by the wife of a Hollywood magnate from Gloria Antika of Brompton Road in the 1940s, presumably shortly after the end of WWII. |

|

Here is a third older – early 19c – creamer with red, with an admixture of black in the sponged coloring. For a rather well molded creamer the painting is quite sloppy – the green of the base carries onto both the hooves and the milk pail and, although you can’t see it, there’s extra paint on the milkmaid’s arm. Its horns are restored, and the right one has been re-attached. The seller indicated that he thought it was likely Yorkshire. |

|

This early creamer with milkmaid has similar red and black coloration on the pearlware body, and also was said to be likely from Yorkshire. It has a strangely colored stopper that is old if not for sure original, and is missing the very tips of the curled up horns as well as part of its right ear. Still looks pretty good for its age. |

|

|

|

Another matched pair, sold as Pearlware circa 1820 by an English dealer from Rugby, Warwickshire. Interesting that the diminutive milkmaids have no pails. Spilled milk? These have had restoration to horns, tails, and one hind leg, as well as replacement lids, but all beautifully done. |

|

This black and purple spongeware creamer with milk person (can't determine if it's a maid) bears a resemblance to those above, wiith horns curled onto forehead. A handwritten note on the bottom says "$750, Portobello, 1840-1860" I think the date is about right, and whoever wrote it apparecvtly got it at the Portobello road market. I paid just $50 for it on eBay - a plesant surprise because it is in prime condition. I have no idea why there was no competiton for it. |

|

|

|

|

This one is somewhat less lovely than those above, but another good example of mid to late 19c Staffordshire, presumably in this case a rather inexpensive one at the time. It has some black ‘cold paint’ – i.e. not glazed – that may have been a touch-up after manufacture. It also has a older restored tail and an old replacement lid, not unusual for one of this period. |

|

This colorful cow with calf is a fairly recent addition to my collection, and is said to be “probably from a Prattware factory in NE England, @1830”. Here the tail, lower lip and lid have been restored; the ‘smushed’ horns and ears survived intact. |

|

Here is another circe 1830 Pratware creamer. Like the pearlware ione above, it was acquied in England by the seller's great aunt while statiuoned there during WWEII. As far as I can tell, this cow is in mint conrition. |

This one was sold on eBay as antique Stafforshire but it is so pristine - except for discoloration of rhe lid - and with gold on the tips of its brown horns that I am tenmpted to think it might well be a reproduction. Its red and blue coloration and the shapoe of the base make me think it might be Welsh, or intended to look that way.. It drew no action on eBay, and at $75 I'm quite haoppy to add it to my collection no matter its age and provenance. /p> |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

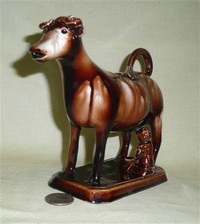

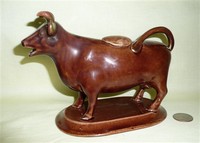

This is a lovely example of a similar form – said to date from the 2nd quarter of the 19c – with a Rockingham glaze of the ‘flint enamel’ type – characterized by the touches of bright color fused in the glaze - on yellowware. There’s a bit about this type of glaze in the Bennington section because it was very popular on American pottery (and the American versions are reputed to be superior to the British ones). A bit of additional information is that this mottled brown glaze has its origins at the Swinton factory on the Marques of Rockingham’s estate near Rotherham, South Yorkshire. The Wikipedia article on Rockingham pottery notes that “After the closure of the works in 1842, some of the craftsmen remained on site to continue manufacturing on their own. The most successful of these was the Baguley family, the most senior of whom Isaac Baguley had been the manager of the gilding department at the factory. Baguley decorated porcelain that was bought in as unglazed biscuitware from other potteries. The classic brown Rockingham glaze was used, the rights to which Baguley had acquired after the closure of the pottery, with much use of gilding and occasional enameling. Baguley eventually moved to nearby Mexborough and the family continued decorating bought-in porcelain there until the end of the 19th century.” |

|

|

|

Here’s another nice Rockingham glazed version from ~1840, with a bit of a different shape but still the curled horns against the head. |

|

|

This is a fine example of a treacle or Rockingham glazed creamer from a mold that is typical of that used for

many of the Jackfield creamers. Other than this one and a similar one with gold on the horns that is in the Jackfield section, I haven't found any of this form that

aren't black. |

|

|

|

This one is similar but without the gold, and it is also shown for comparison on the Jackfield page.. |

|

I acquired this large pair in an antique shop on the old walls of Chester. They seem to be made of reddish earthenware coated with Rockingham glaze. These have large teats and, what I find most unusual, small rectangular mouths. The seller indicated that they were mid-1800s but per usual had no further information. As always, I’d welcome help. |

|

This one that came from a collection of a lady in New Jersey is essentially identical to the pair from Chester, albeit I didn’t recognize it as such from the picture on eBay. While she may indeed have acquired it on a visit to the UK, the glaze is also quite similar to American Rockingham as described on the Bennington page, and I am aware that some with this glaze were made in Pennsylvania. I do however believe that it is British. |

|

|

|

|

|

I’ve seen quite a number of these, and they’re often referred to as having a ‘Majolica’ glaze. The horns and ears are gilded, again as is common with the Jackfields. Like many others, it was simply dated by the seller to the 19c. This may have more to do with US import tax rules than anything else… |

|

Here’s a caramel colored one quite similar in shape and style. It’s had a fair amount of restoration, horns, ears, and lid. |

|

I'm not sure this one is English let along "Staffordshire" but it's made of red clay under the bright copper lustre glaze, and it's for sure not from China or Japan. It looks quire similar to some Italian molds, but I don't recall any of them being made of red clay so I stuck it here. |

|

|

This white one – most likely from the late 19c Victorian period – is in good shape and shows signs of some considerable use since much of the gilt has rubbed off. It was surprisingly inexpensive for a creamer of its vintage…probably as much of a surprise to the seller as to me. |

|

|

These two are definitely not “Staffordshire” in the sense of being from one of the early potteries, but they are indeed English. The brown one was sold by a knowledgeable dealer as ‘Late Victorian’, circa 1900, whioch seems right to me. The black one is also shown on the Jackfielkd page because of its glaze. They are interesting to me on two counts: first the curly hair, which I believe is intended to make them look like a Scottish Highland cow. Second is the fact that the brown one is stamped with a registration number, “Rd No 445,059”, and there is a similar but undecipherable mark on the black one. I would like to learn more about the use of these numbers, since these arethe only ones in my collection so marked. |

|

|

|

|

This is another very sprightly, non-traditional and somewhat unusual cow creamer – said by the knowledgeable UK antique dealer seller to be circa 1850. Except for a re-glued horn which is almost undetectable it’s in fine shape. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Here are three versions of old English ceramic cow creamers that are really quite different in style and make-up from those above, and must have been designed to be more utilitarian than beautiful. They were probably also quite inexpensive when first sold (unfortunately not now). The two that are similar both have some damage to the horns – I have yet to find one from this mold that hasn’t suffered in some way or another. I have no further information about them except that the one with the white base and bark brown spots was said by the seller to date from the 1830s. I would guess that they’re all pre-(or very early) Victorian, since items from that era tended to be significantly fancier. |

|

|

These two white cows with yellow horns and blue flower decorations come from the same or very similar mold to the one on the left just above. The only real difference other than color is the base. These two both have light underglaze crazing, and the one in back has lost the tip of her left horn. |

This cute cow with the pink and white flowers is here because its eyes are very similar to those above. I have no idea if it is Stafforshire, or perhaps even from Italy. It has a cork to hold on the lid, and on the base has either "15" or "IS over an "R" written in in red. The seller only coultd tell me that she bought it because it was pretty, back in the 1980s or so. It's definitely quite modern., but nicely done and very modest witth only little red dots for teats on a very small udder. | |

|

|

|

The seller said this one dated from @1820. It has glossy glaze all over including the bottom of the base, and it has seen a hard life - restored lid, repaired and partially restored tail, repaired and restored horns. I found the slightly protuberant and outlined eyes interesting, and the price ($58 including shipping from the UK) was eminently reasonable, so it now is catching dust with the rest of the herd. |

|

|

This one has more than minor damage, and could use the assistance of a professional restorer – it’s missing its right ear and has 3 legs and one teat re-glued (ouch). It was unusual enough (and inexpensive as these things go these days) for an early 19c creamer to attract me however – finely molded, painted and glazed, and with no base. I looked the hoof bottoms over carefully, and the best I could tell, it’s never been mounted – which would seem to explain the damage to the fairly delicate legs. |

|

This is a very strange variant – included here because it did indeed come to me from the UK, and was dated by the seller to early 19c. It’s fashioned of heavy reddish earthenware and has a green tinted glaze, most noticeable on the udder. It’s fairly crudely made and has a number of firing cracks. The horns have been replaced, and one of them was then broken at the tip. Nonetheless a very interesting example, and certainly quite early. |

|

I’m not quite sure what to make of this one – it has the horns curled against the head which would suggest to me a late 19c date, but at the same time has the lid incised into the back, which is more typical of much earlier creamers. It has crazing all over which is not normal for early English earthenware. The seller, who bought it in the 1980s at a Harrogate antique fair, said she thought it had a base at one time but I see no indication of that. It’s possible that it is a 20c ‘reproduction’, but at least it was reasonably inexpensive, displays very nicely, and is different from my other creamers of this general type. |

|

|

Next come a whole bunch of an extremely popular form of Staffordshire cow creamer, still (or at least until quite recently) being produced. I have chosen to dub them "Kent" style after one of the many factories that made them, as discussed on the Favorite Brands page. This is a modern one, which we bought at The Potteries Museum and Art Gallery in Stoke-on-Trent when we visited around 1996 to view the famous Keiller collection. Kent stopped making these in 1962, but the museum had some reproduced (with the Kent knot logo) in a variety of colors for sale in their gift shop. I opted for the green one, although as shown a bit below we did find one iu more traditional brown and white colors while wandering around the town. |

|

|

|

|

Here are several more examples of the "kent" style creamer In the picture of the four without bases, the two with the purple luster bear a orange stamp that I believe says Wade, England (blurry, and the rest is obscured). Wade was established in 1810 in Burslem, the town that’s the headquarters of the pottery industry in Stoke-on-Trent, and is best known these days for a small solid ceramic animal collectors set called ‘Whimsies’ that came out in 1953. Their website (www.wade.co.uk) didn’t return anything for a search on cow creamer, so I don’t know if these are really from them, but again this is a very popular mold, and has been made by a number of potteries in the area. Again see, e.g., Kent on the ‘Favorite Brands’ page. The creamer with the reddish markings between the two purple ones has “England” in script on its belly; and for comparison I’ve included a modern one manufactured by the Kent factory between 1944 and 1962; it bears the William Kent logo of a knot with W and K in the loops, “Staffordshire Ware” above and “England” below, and the initials of the artist who decorated it. The other two pictures show more examples, including one with a blue-willow transfer, a rather crude one in the middle of the second picture, and another Kent model, the cow with bouquets of blue flowers on flanks and forehead and the raised flower on the base, which is also typical of a large number of creamers. |

|

|

|

|

We bought these two in England when we lived in London in the mid-90s, fairly early in the period of upgrading the collection from just a few costing less than $10 each, to being much more includive and learning a bit about those that were made in England. The one on the left came from an antique shop in Hanley, Stoke-on-Trent, when we visited to see the Keiller sollection in the museum there. The other was purchased about a year earlier, in the famous Bermondsey Market, and was probably the first of my 'Kent' cow creamers. That market had a reputation of being a good place to look for British antiques, but over time I have learned that the prices there weren't any bargain. Both of these cow creamers have the Kent knot logo with "Staffordshire Ware" above and "Kent, Made in England" below. My guess would be that they date from shortly after WWII. |

|

|

These two, like the ones just above, bear the Kent knot logo with "Kent" beneath the knot. They came to me (via ebay) from a NC estate where the seller said the person had some 3000 cow items. I was delighted to find these, because they are my only for-sure Kent ones that are very different in form. They each have a bit of damage, but still display (and pour) beautifully. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

This one – again with the same style cow – is interesting because it has the horns, ears, and 3-slash gold gilding that’s typical of Jackfield creamers. |

|

This one is pretty obviously even more Jackfield-like, with the black coloration and gold gilding. It could and perhaps have gone on the Jackfield page, but there's already one like it there so I put it here to emphasize the wide use of this very popular mold. |

|

|

|

| |

These two are modern reproductions, reflecting a continuing appreciation for this very popular and common form. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Here is a fifth example of a cow creamer with a Chinese transfer print. I believe this one is somewhat earlier than those just above - probably @1840 - based on a combination of the circular transfer print and the fairly high oval base with crude raised flower. |

|

In contrast to the cow-and-person figurines which are typically made of heavy ceramics, this is a porcelain creamer with the fill hole in the back of the cow. It is basically in the form of the spill vases shown below, but certainly not designed to hold spills so it must have been intended as either a creamer or simply a decorative piece. It’s very finely made and painted, but has no marks and I have no information about its age or maker, although I expect that it is fairly modern. |

|

This is an earlier and more important porcelain piece, dating from @1865, which I acquired at a London antique fair in 1997 and about which I have at least a bit of information. The mark on the base shows that it was made by the partnership of Stevenson and Hancock, which began in 1863 and operated in Derby. From the web site www.derbyporcelain.org.uk we learn that “The Old Crown Derby China Works, or as it is better known these days, the King Street Factory, ran from 1849 until 1935, when it was taken over by the present Royal Crown Derby Porcelain Co. Ltd., and closed down. It formed an historic link between the earlier Nottingham Road factory and the current works on Osmaston Road, Derby. On the closure of the Nottingham Road factory in 1848, six workers from there set up a china manufacturing business in rented premises at 26, King Street, Derby. Of the various proprietors who ran this concern over the years, Stevenson and Hancock are the best known. Their initials formed part of the main factory mark of a crown over crossed swords and D, with two sets of three dots and the initials S and H, which continued to be used after the deaths of both Stevenson and Hancock, in fact right up to the closure of the factory. The factory produced both decorative ornamental wares as well as useful china and offered a replacement service to customers who had broken pieces that they owned. Shapes and patterns used earlier at Nottingham Road were repeated, as well as turning out entirely original wares. A few products, mainly figures, were made in unglazed biscuit, but the bulk of the output was in glazed white or in enameled form, all of the latter being hand painted.” There’s more history of Derby pottery and S&H at http://richardgardnerantiques.co.uk/page/818/Derby. I would imagine that porcelain cow creamers were relatively rare, since the creamers were primarily utilitarian items and porcelain was significantly more expensive than earthenware. Indeed, the books I’ve read indicate that many earthenware figures were modeled after porcelain ones, but intended for a lower priced market. I find this cow to be a particularly lovely example – the stand or plinth underneath the belly was intended to keep the soft porcelain from drooping during firing. Unfortunately it is missing its lid that also has the tip of the tail, as shown in the glazed versions below |

|

|

|

|

Here is a, unmarked glazed white ceramic version from the same or similar mold as the Stevenson & Hancock porcelain creamer, said by the English seller to be from the 1890s. It seems that S&H wasn’t the only firm to employ this or similar molds, although this one seems to be a bit unusual in having been fashioned in both porcelain and sturdier clay. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Here’s another creamer with calf from the same mold and bearing the C. Cooke, Staffordshire, England mark. |

|

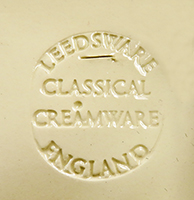

I believe this large cow with a calf is also quite modern. It is clearly impressed for “Leedsware Classical Creamware, England”, and there is an interesting story here. From www.worldwideshoppingmall.co.uk’s section on pottery we learn that “Brothers' John and Joshua Green in partnership founded LEEDS POTTERY in Leeds in 1770 with Richard Humble. Success soon came with the production of household goods in a variety of ceramic bodies, the most popular being CREAMWARE, a type of earthenware made by several companies from white Cornish Clay with a translucent glaze, producing the pale cream colour from which it took its name…By 1781 William Hartley had added his design and business expertise to the Green brothers' production skills and under the name Hartley Greens & Co the company flourished, expanding its trade across Europe and into Russia. Such was its success that from then on Creamware would also be known as Leedsware. In the 19th century after the death of its founders the different tastes of the Victorian era brought a gradual decline in business, leading eventually to the Pottery's closure in 1878. Despite the later demolition of the kilns and buildings, surviving moulds and clues from pattern books together with fine examples of Leeds pieces in local museums enabled production of Creamware to the original designs to continue to this day.” In trying to track down the manufacturer of my version I learned (from a kind person at Hartley Greens) that the old Leedsware molds were sold off by the Leeds City Council around 1988 in two lots. One lot was purchased by Hartley Greens (which has a nice history of Leeds Pottery on its web site), and the other by Classic Creamware, which in turn was bought out, although the company that bought them no longer makes creamware. So either my creamer is 18c, which I doubt, or it’s only a couple decades old and the mold for it is still around, somewhere. Help please, anyone?? | |

|

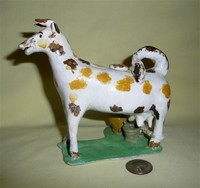

Here is a colored version of this same Leedsware Classic Creamware cow and calf. |

|

|

Yet another, which I acquired largely because of its peculiarities. First, the calf is facing in the opposite direction. Second, the top of the base has been painted green, over the glaze … and third (which I didn’t notice till it arrived), the “Leedsware” impression on the bottom of the base has been filled in and painted over. Hard to know why anyone would do this, but the seller who had acquired it in that condition didn’t try to mis-describe it, just said it was ‘vintage Staffordshire’ and offered it at a very low price. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

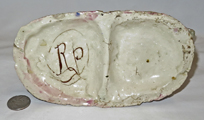

Finally, here are a couple ‘sports’, about which I have little to no information. The one on the left would appear to be modern (and bore a very modest price tag). The wacky cow on the right, which came from the UK via eBay, was called ‘Faience’ by the seller. The flowers and leaves on its sides are raised, the lid is cut into the back (like my very early Whieldons), and the base bears a hand-done monogram of an overlapping T and R. It is certainly very different from any of the others. |

Welsh Ceramics and Swansea PotteriesThis introduction is derived principally from “Welsh Ceramics in Context, Part 1”, edited by Jonathan Gray and published by the Royal Institute of South Wales with support from the City and County of Swansea in 2003, supplemented by several articles from the web. Swansea is located on the southwest coast of Wales, in what was then the county of Glamorgan (Glamorgan has been significantly reorganized several times – the potteries discussed here were in what is now the City and County of Swansea*) at the sheltered mouth of the river Tawe. With its navigable river, decent harbor, access to local and overseas markets and abundant local coal, Swansea has been a center of trade since Viking times. With the coming of the industrial revolution it was a logical center for the development of copper smelting, and this began in the Tawe valley near Swansea in 1717. By the end of the 18c eight smelters had been founded within three miles of the town (making a mess downwind), and given the advantages of cheap coal and easy transport by sea, many other industries followed. One copper smelter near the town was established by James Griffith in 1720. When the lease on the ground of this older copper works was surrendered in 1764, it was taken up by William Coles and his partners, to establish a pottery. There had traditionally been a simple earthenware pottery tradition in the area, but this was the first attempt to establish a larger and more ‘modern’ manufactory. Industrialization had created a demand by the more wealthy segments of society for fashionable wares and for finer ceramics such as were being imported from China and the continent. Developments in Staffordshire, particularly those by Josiah Wedgewood - both by emulation of technique and by the availability of skilled specialist workers - formed the basis for this Welsh expansion that was designed initially to meet the needs of the local market. It took several years to demolish the old copper works, hire the needed experts, and erect the kilns and other facilities for the new trade, but production began in 1767. By 1771 this pottery had hired a master potter from Staffordshire and was producing both saltglaze and creamware bodies. William Coles died in 1778, and the pottery struggled (as did many such industries in that era) until Coles’ son was joined by George Haynes, who had lived for several years in Philadelphia. In 1790 a fresh lease was taken for them in partnership. Haynes, who had initially come back to England thinking of retirement and likely remunerative investments, soon was deeply involved in what was then named the Cambrian Pottery, and became its manager. Haynes is credited with considerable upgrading and expansion of the works, as well as attracting a talented engraver, Thomas Rothwell, to produce transfer printed as well as enameled wares. The pottery benefitted from the reopening of trade with America coupled with Haynes’s Philadelphia contacts, and it thrived in the 1790s. Swansea continued to profit from developments in Staffordshire, particularly those by Wedgewood; and it is not unlikely that cow creamers, as well as other tea and dinner service items and a widening range of wares, were produced there during this period. In 1799 Edward Coles died and the Coles’ assets were assigned to Haynes. In 1801 the American Quaker and merchant William Dillwyn visited Swansea, then returned in June 1802 to make an arrangement to buy part of Haynes’s interest in the pottery on behalf of his son, Lewis Weston Dillwyn. Haynes initially remained as manager, with day to day supervision of the works by Edward Green and the firm’s agent Thomas Belington (who became a partner in 1811). Lewis Weston Dillwyn was primarily a naturalist and spent most of his time in London, thus being a largely absentee proprietor. This worked well until 1809 at which time relationships between Dillwyn and Haynes deteriorated badly and Haynes departed in 1810. Haynes had surreptitiously acquired a lease of foundry buildings adjoining the pottery, and established a soap works there. This was an extremely smelly business and had a very adverse impact on Cambrian’s workers and customers; Dillwyn was convinced this was malicious, took legal action and won the case. Haynes then established a rival pottery, the Glamorgan, adjacent to the Cambrian. Haynes initially financed as well as managed the new business, then brought in his son in law William Baker, and as well as two other financial partners, Bevans and Irwin. This accounts for the “BB&I” mark which was used on their wares, which were made largely for domestic use. There were no effective patent or copywrite laws in those days and many of Haynes’s workers followed him, so the new firm produced lines of transfer printed and enameled creamware and pearlware that were very similar to those of the Cambrian, albeit with some differences in molds and technique. Haynes died in 1830 and the Glamorgan languished through the lack of his experience, finally being sold in 1837 following the loss of Baker and the bankruptcy of Bevan’s Iron Works. It was purchased by Lewis Llewellen Dillwyn, Lewis Weston’s son, who had run the Cambrian since 1836. He then sold most of its assets to the man who used them to help establish the ‘South Wales Pottery’ in Llanelly. Competition from this new venture helped lead to the ultimate demise of the Swansea pottery in 1870. The Swansea cow creamers – a very minor part of the business just as in Staffordshire – were all creamware or pearlware, as far as I know. However there were many attempts in Wales to produce competitive, high quality porcelain – both at the Cambrian under Lewis Weston Dillwyn from 1814-1817, and by the celebrated china painter William Billingsly who had spent many years at the porcelain works in Derby, at Nantgarw as well as with Dillwyn in Swansea. Although the basic ‘recipe’ for this prized ceramic had been available in England since around 1765, it was exceedingly challenging to produce regularly and at reasonable cost due to kiln losses, and this industry never fully succeeded in Wales albeit the pieces that were produced were of very high quality.

"Administrative map of the County of Glamorgan in 1947" |

|

|

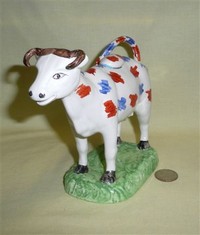

This is a modern (but made with traditional hand-crafted techniques) reproduction of a Swansea, Cambrian cow creamer from the early 19c. It serves here as a good example of this factory’s cow creamer molds, as well as their typical red and blue enamel coloration. I have learned quite a bit about this handsome reproduction creamer from a very kind collector who inherited one from her mother (who in turn received it from the managing Director of Beefeater UK Ltd who obtained it as a gift in 1988). Mine is #106 of the 200 produced by the Gladstone Pottery Museum, which is located in Longton, stoke-on-Trent, Staffordshire and is a working museum of a medium-sized coal fired pottery, typical of those which proliferated in the area starting in the 18c*. These limited edition creamers were commissioned in 1987 by Express Foods Group, Ltd to commemorate the opening of a new ultra modern cheese packing factory in Oswestry which was opened by HRH the Duchess of Kent. My cow-respondent noted that Empress Foods “appear to have been acquired by Diageo CL3 Ltd in January 2011 who then changed their name to Diageo CV Ltd and are now based in Park Royal, Greater London. It isn't clear whether they still manufacturer food based products.” A web search turned up the information that “Diageo is a global leader in beverage alcohol with an outstanding collection of brands across spirits, beer and wine categories. These brands include Johnnie Walker, Crown Royal, JεB, Buchanan’s and Windsor whiskies, Smirnoff, Cîroc and Ketel One vodkas, Captain Morgan, Baileys, Don Julio, Tanqueray and Guinness.” I will admit to having sampled a number or their products…but I wonder what they did with the cheese factory.

|

|

|

|

|

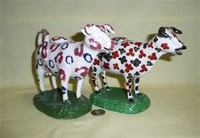

This is a very similar pair, or at least bought together - in this pair, both have horns that sweep upward, and one is without the red splotches and its purple spots seem to be lustre. |

|

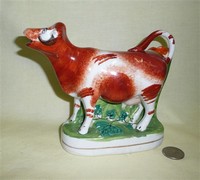

Here is yet another example of the typical Cambrian cow creamer, this time with brown horns and blue and red splotches. |

|

|

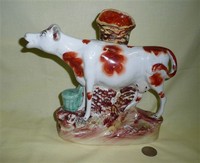

Both Glamorgan and Cambrian potteries produced cow creamers, and given the connection between the two via George Haynes it’s not surprising that they were quite similar. Here is a good example with which to compare of the differences, as described in the “Welsh Ceramics in Context” book and (although I can’t find the reference recently) the web site of the Swansea museum: The key feature is the brisket or breastbone, which is pronounced and protrudes downward on the Cambrian cows - here the one to the right – and is more slender on Glamorgan cows. The Glamorgan ones also had a squarer head. Another difference is shown here – the Glamorgan cows were commonly transfer printed with a rural fishing scene, and were marked “Opaque China over “BB&I”. The term, “opaque china” is attributed to Haynes, who coined it for the fine white earthernware from the Swansea potteries. Apparently most of the Cambrian cows had the red and blue enamel like shown above (more examples follow), or patches of pink luster. Examples of both of these creamers are shown on p.112 of the cited reference, and it notes that the few Cambrian ones that were transfer printed had this design of shells and flowers. I would imagine that at least the fishing scene, and perhaps the flowery one, were from engravings by Thomas Rothwell. They are nicely applied on both of these cows, and I’m delighted to have these examples in my collection. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

Here is a close mate that bears typical Swansea coloring – pretty badly beat up with lots of restorations, but acquired at what – for these early creamers these days (2014) – was a quite reasonable price, under $100. And of course one never really knows what shape they’re in until they arrive. |

|

|

This one also came from Jacqueline OOsthuizen’s London shop in 1997 – They said Swansea ~1850, which would put it for sure from the Cambrian works, after the closure of Glamorgan. It and the few that follow below are very differ from those from the earlier molds – not surprising that tastes would have changed over 30-40 years. This one is missing its base – although it has touches of green on some of the hooves, to me a pretty clear indication that it once had one. I was fairly early in my collecting in those days, however, and didn’t notice that till much later. I probably still would have bought it as a nice example of a somewhat later Swansea cow. |

|

|

I acquired this one via eBay from a UK seller some 15 years after I bought its close cousin abvove - and I think it confirms my suspicions about that one having lost its base. This one also has green on the toes - apparently the 'artist' that painted it wasn't overly careful - and one hoof is nearly detached from the tall green base. The base is actually quite unusual - the tallest I have seen. It has a cracked and repaired lid but is otherwise in prime condition. |

|

This lovely Swansea cow creamer has a very similar shape, and also has a fairly tall base. The bronze lustre is interesting - I don't recall reading about when it became available or popular. This cow has had some damage - missing one teat, broken left horn and restored right horn, but the coloration was so different that I couldn't pass it up. |

|

This creamer is somewhat smaller that the ones above, and has a differently shaped head. Its reddish-brown markings are rough to the touch, and have been added on top of the glaze. The right horn and ear are a bit shortened, but I believe that was a fault in the making and not a later break. It also sports world-class teats, that seem to spring directly from its udderless body. Interesting interpretation. |

|

|

Spill Vases |

|

|

Introduction. Friction matches like we’re used to today weren’t manufactured – if that’s the right term – in England until around the 1820s. Even then, for decades they were much too expensive and rare for routine use, so people used or slivers of wood – sometimes specially shaved for the purpose – or more dangerous paper tapers to transfer fire and light lanterns and cigars or pipes. These fire-starters are called ‘spills’, and because they were needed frequently, folks would keep a bunch of them in a vase that usually sat on the mantle. In the grand British tradition, utilitarian items like spill vases morphed into fancier wares that were also decorative, especially during the Victorian era, providing yet another market for the inventive Staffordshire (and other) potteries. Naturally enough, topics that were already popular as Staffordshire figurines – including cows, milkmaids, dogs, horses, etc – became decorations for spill vases. The pair shown here – small decorative porcelain bisque versions dating from around the 1870s – are not atypical. While these two which I’m using to introduce this sub-theme do have cows, the cows are solid. In many cases however, cow creamer molds were modified and pressed into service as the decorations for the spill vases…and indeed, I’d guess that if you weren’t fussy you could use them for either purpose. |

| Here are two typical spill vases from the late 19c - in this case the hole for the spills, or for cream if they were to be used for that purpose, is on the top of the milkmaids' heads. Since these were made to sit on mantles, their backs are almost invariably flat and undecorated. | |

|

|

|

This one is a bit unusual in that the boy is sitting on some sort of bench or stone next to the tree, rather than standing next to his cow. The cow has lost a bit of its paint and has an old chip inside its upper lip, but it’s otherwise in fine shape and was reasonably priced. |

|

|

|

| Here are two typical spill vases from the late 19c - in this case the hole for the spills, or for cream if they were to be used for that purpose, is on the top of the milkmaids' heads. Since these were made to sit on mantles, their backs are almost invariably flat and undecorated. | |

|

These two cow creamer spill vase combinations are identical in style but of slightly different sizes - with flat backs and a hole in the top of the milkmaid’s hat. |

|

Another fine, traditional spill vase with cow creamer, tree and milkmaid. |

|

|

|

Like the one above, this creamer or spill vase has a flat back, and a fill or spill hole in the top of the maid's head. The cow is nicely sponge painted in dark brown, there are five groups of little raised bristly flowers on the base, and the dainty decorations on the maid's skirt are exquisite. It's very pristine (small chip to the back of cow's left ear, but dark brown and under glaze), so I wondered if it might be a reproduction. It was sufficiently inexpensive to so be, but it seems very well executed, the seller got it from the estate of a major colletor who 'loved his cows' and kept it behind glass for 40 years; and if it just sat on a mantle before he got it, it wouldn't have seen the hard use of a regular creamer. So I accept it as genuine 19c. It is quite lovely so even if I'm wrong, it is a nice addition to the colletion. |

|

|

This one with a boy tender and a very sprightly faced brown and white cow is also quite pristine. I sense that these spill vases that were never actually used to hold spills have had good treatment for a long time. They simply don;t sell for enough, or in large enough quantities, to justify reproduction |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

This is the only spill vase cow creamer combination I’ve seen featuring a cow that is lying down. That gives it the practical advantage of being very stable. It has the typical flat back as well as a wide mouthed spill holder, and is certainly designed to also serve as a creamer. It is very nicely crafted and painted, and appears to have crackling under the glaze. It came to me from Swansea in Wales, although I don’t know if the cow was actually made in that area. The seller, with whom I exchanged some pleasant notes that ultimately led to my longish discussion of the changes to Glamorgan County in the footnote to the introduction to Welsh Ceramics, simply said it came from the estate of a well known local collector. There is a spot on the base that looks like it might have been a mark of some sort, but it’s completely illegible. |

|

This large spill cow creamer, in fine condition, appears to be from the same or a very similar mold as the one above, with a standing milkmaid added. It was acquired from A&N Harding Victorian Staffordshire, based in Dover, England (albeit it was mailed from Jersey). For those interested in fine Staffordshire Figures, as well as informative books about them, try www.staffordshirefigures.com. |

|

Here are two more examples featuring the same cow as those above, with sitting milkmaids that are identical except for their location. This is a very good example of how the potteries maximized the use of their molds to produce a number of variations using identical basic parts. This combination seems to have been a fairly popular version since I have seem quite a few variations for offer on eBay. |

|

This is a pleasant and interesting variant. It actually breaks my rules since the cow has no holes – but it was very inexpensive (for such things) and is designed to be a very efficient spill holder. A knowledgeable seller indicated it’s from around the 1890s, and from William Kent Staffordshire. For a very interesting introduction to such Staffordshire figures with a bit about Kent, see https://madelena.com/introduction-staffordshire-pottery-figures.php |

|

This is indeed a cow spill vase, but it's really small (a bit over 3" each way), and there is no pour hole in the cow. It is German bisque porcelain, hand painted with a mold #118 on the back of the base. I bought is because it's something that was new to me - a "fairing" which refers to these small figures that were farground prizes as the fairs toured around the Uk and Europe. The knowledgable seller says it dates to around 1860 - these were apparentky very popular in Vistorian times. The early ones were hand painted and unglazed like this one, and later ones were glazed, often with sayings. It is very well molded for a 'prize' - and no longer a give-away I assure you. Pricey little thing but I am delighted to have it, |

|

|

Apparently spill vases are still sufficiently popular as ‘collectibles’ that folks have decided to make reproductions. The orange and white one bears a small ‘Made in China’ sticker, and the one with the boy at the aft end of his cow, while not marked, is clearly very modern. So per usual, buyer beware…especially on eBay where sellers often don’t know what they have. |

|